Peter Vahlefeld

How Do We Read Images?

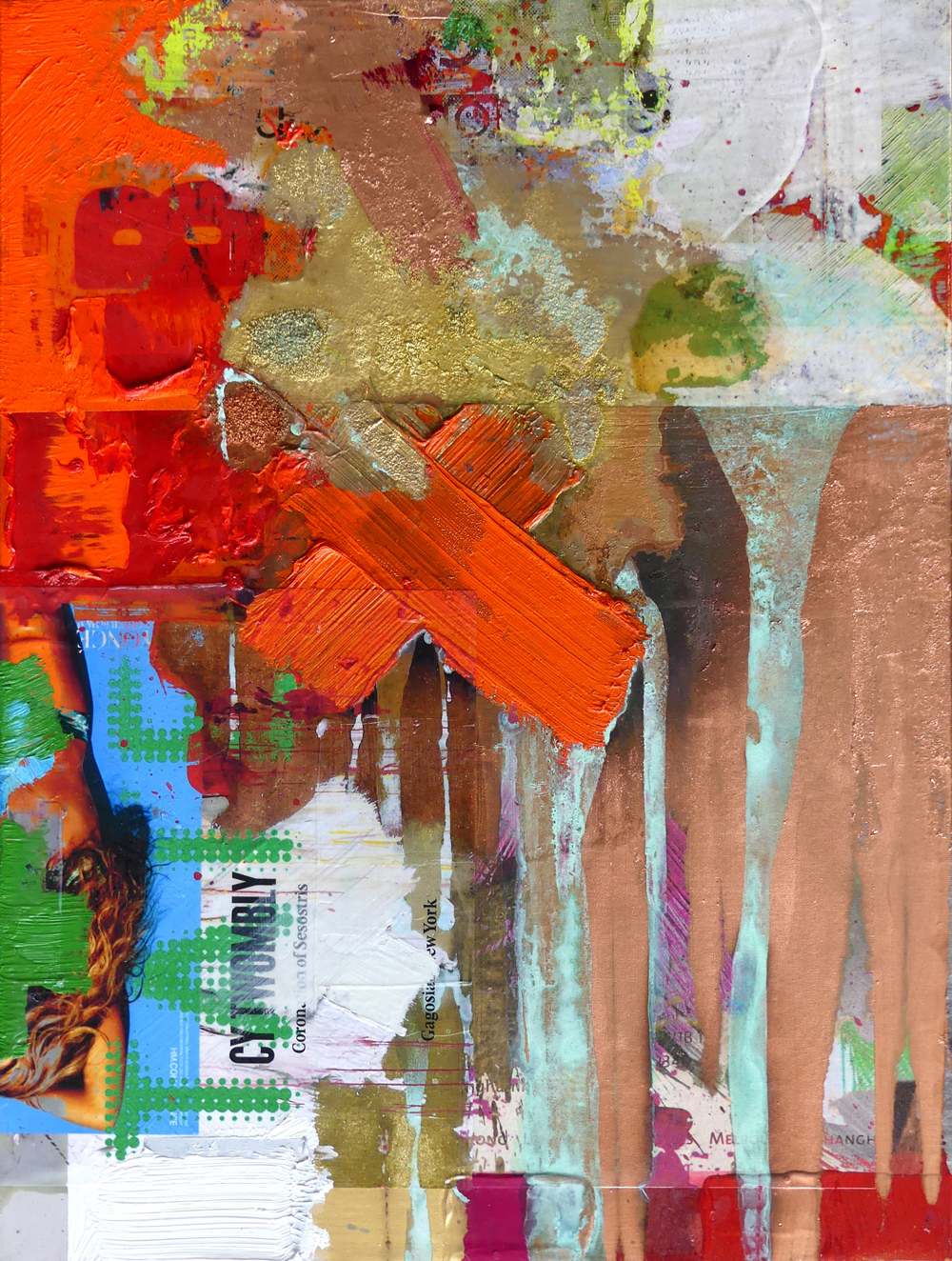

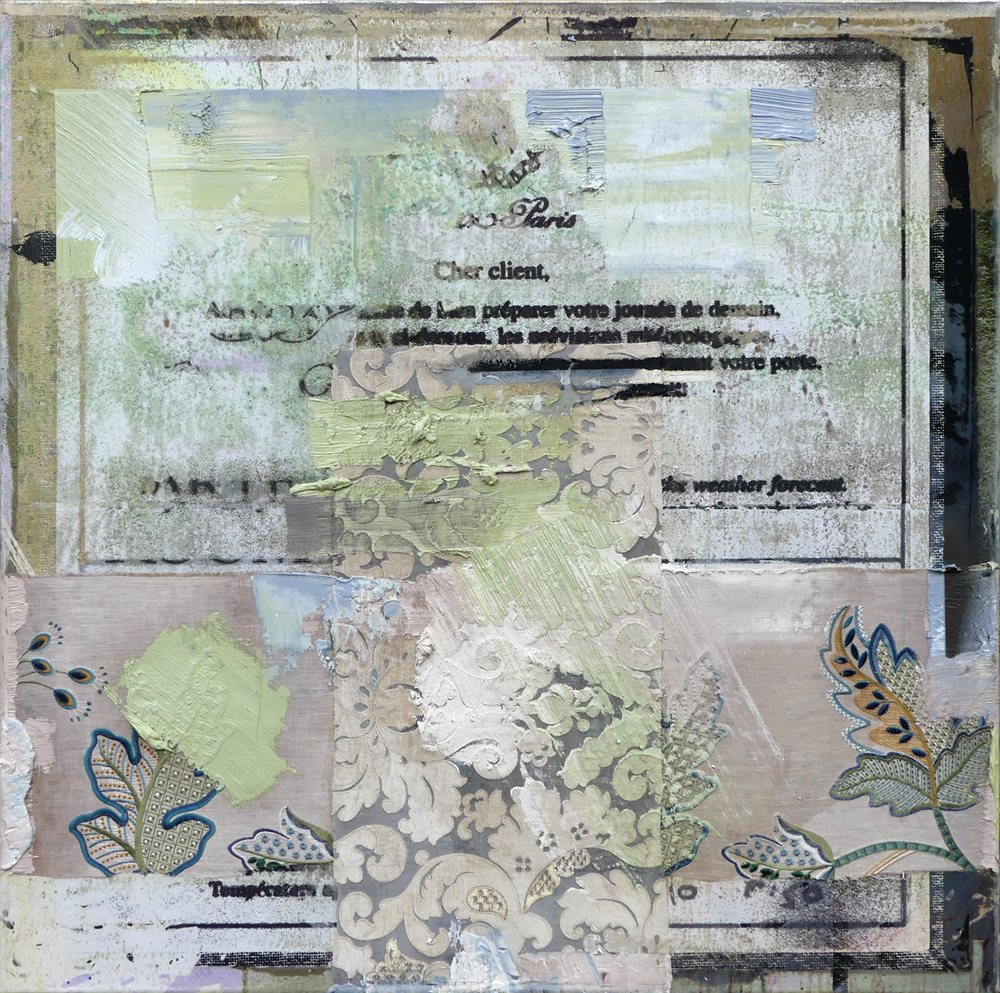

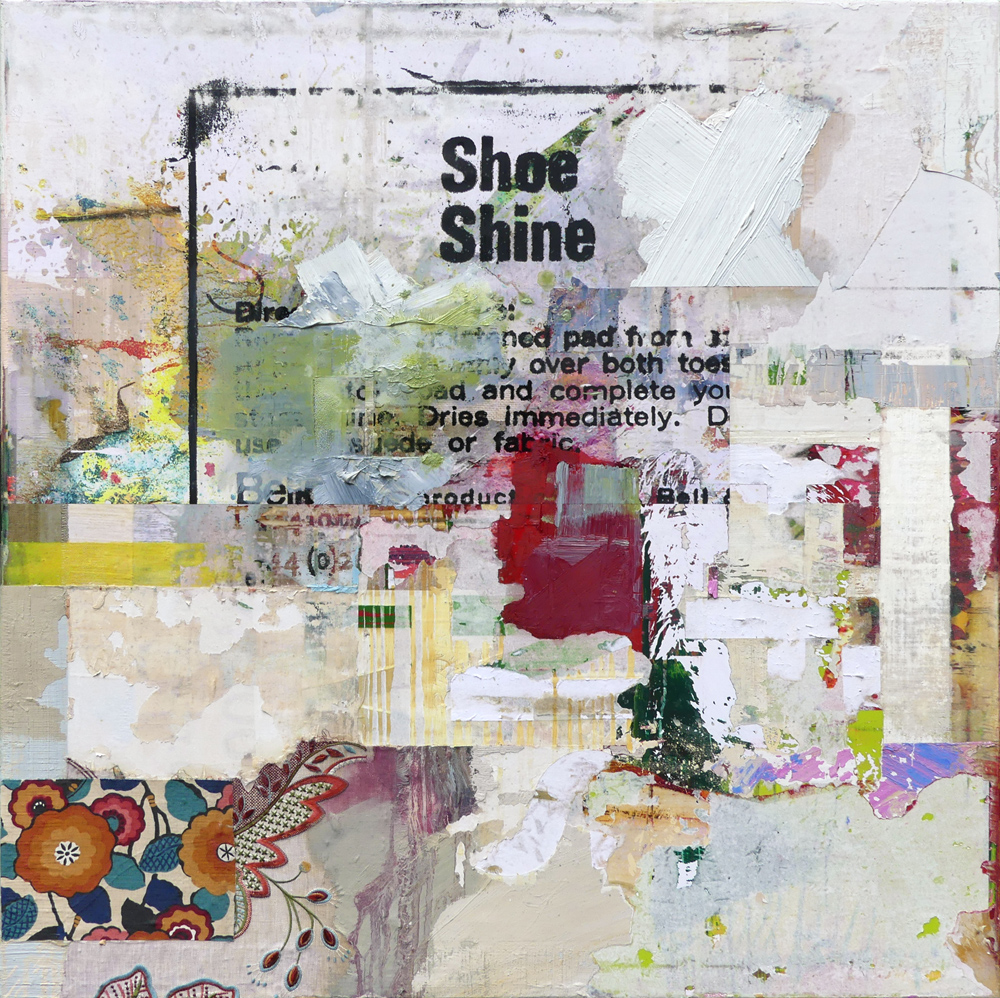

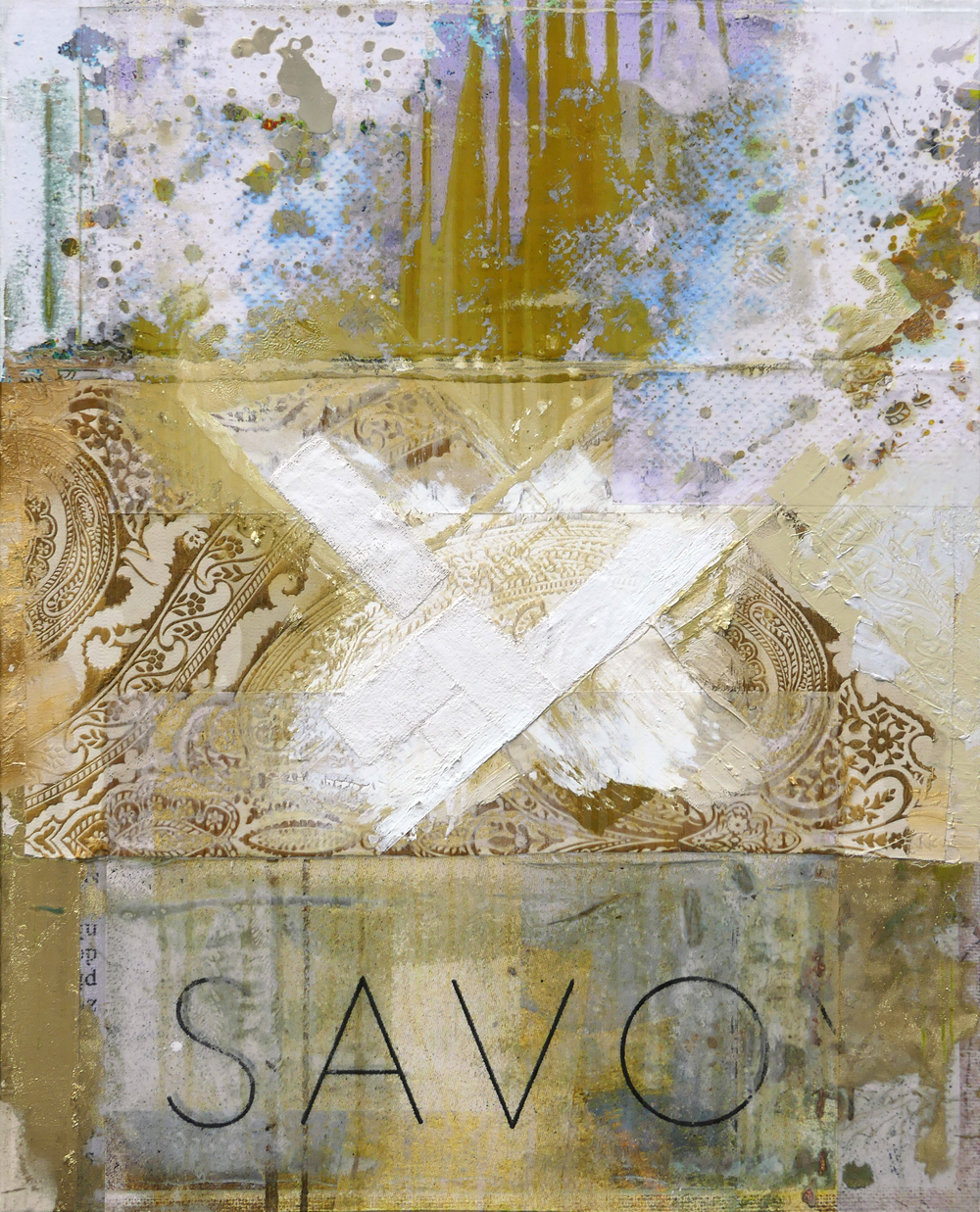

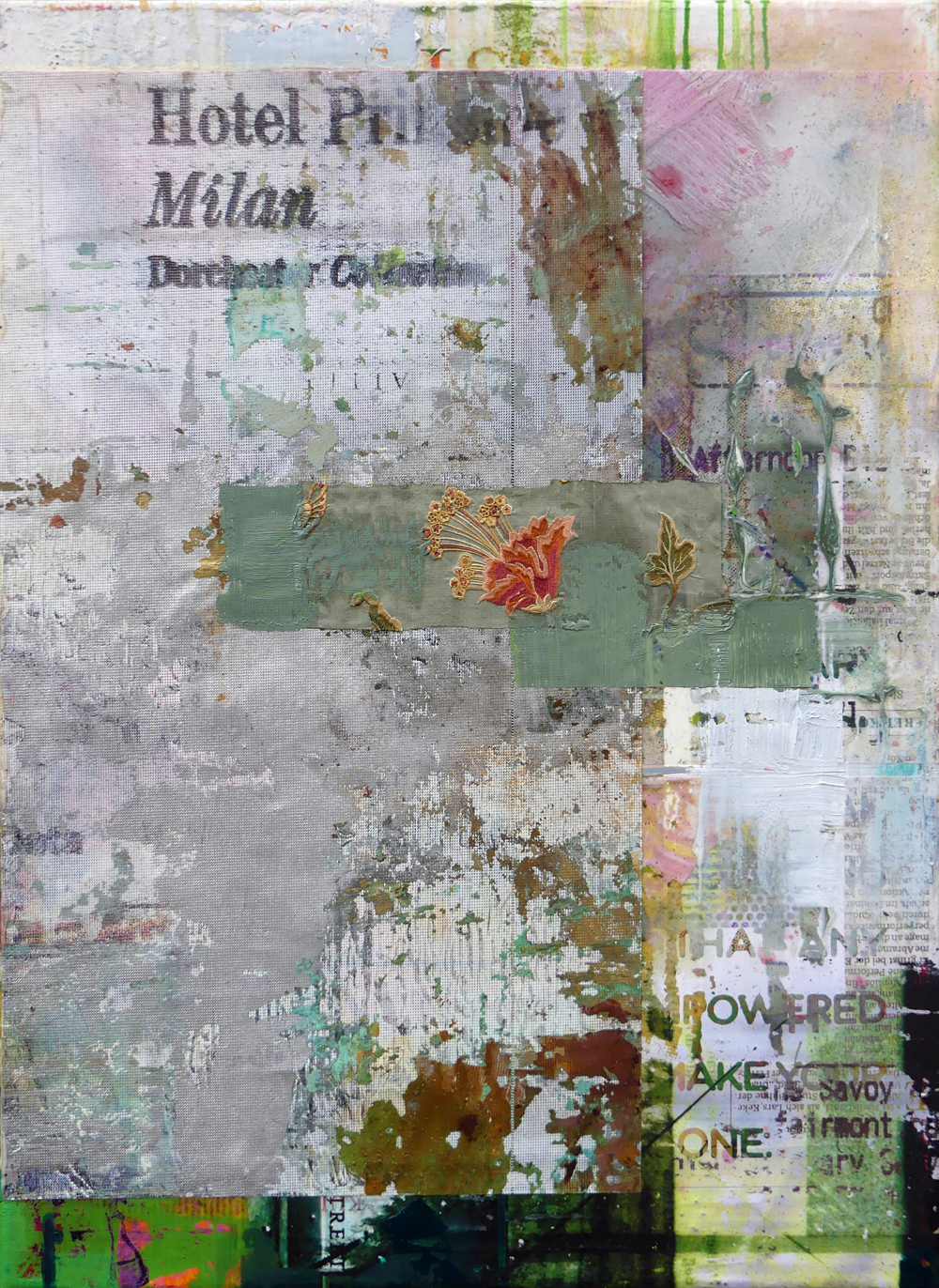

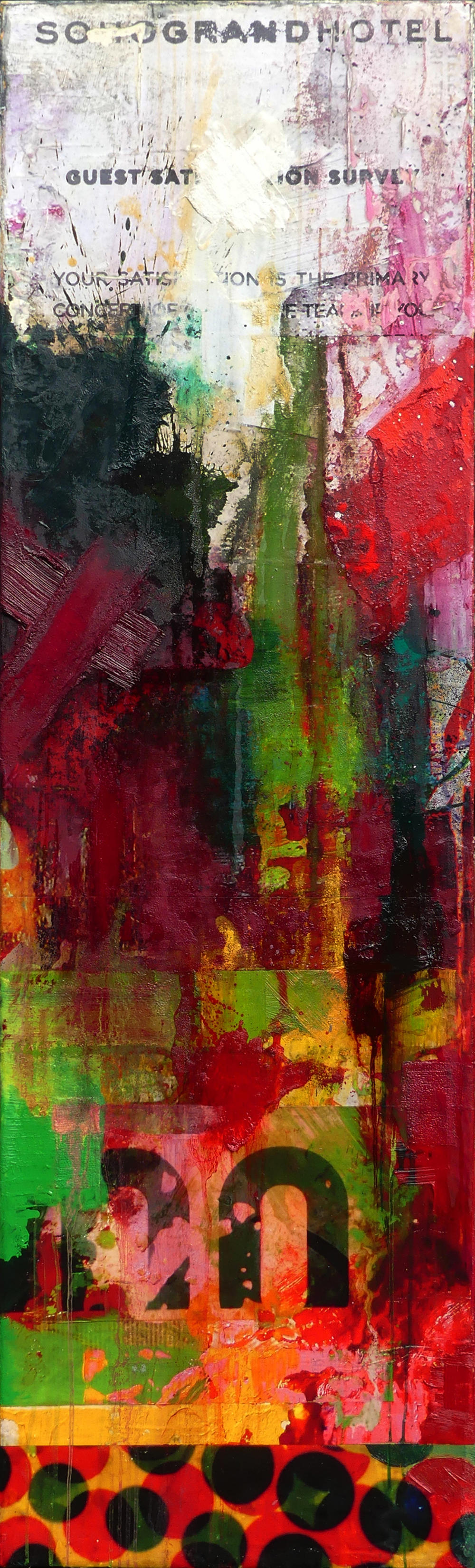

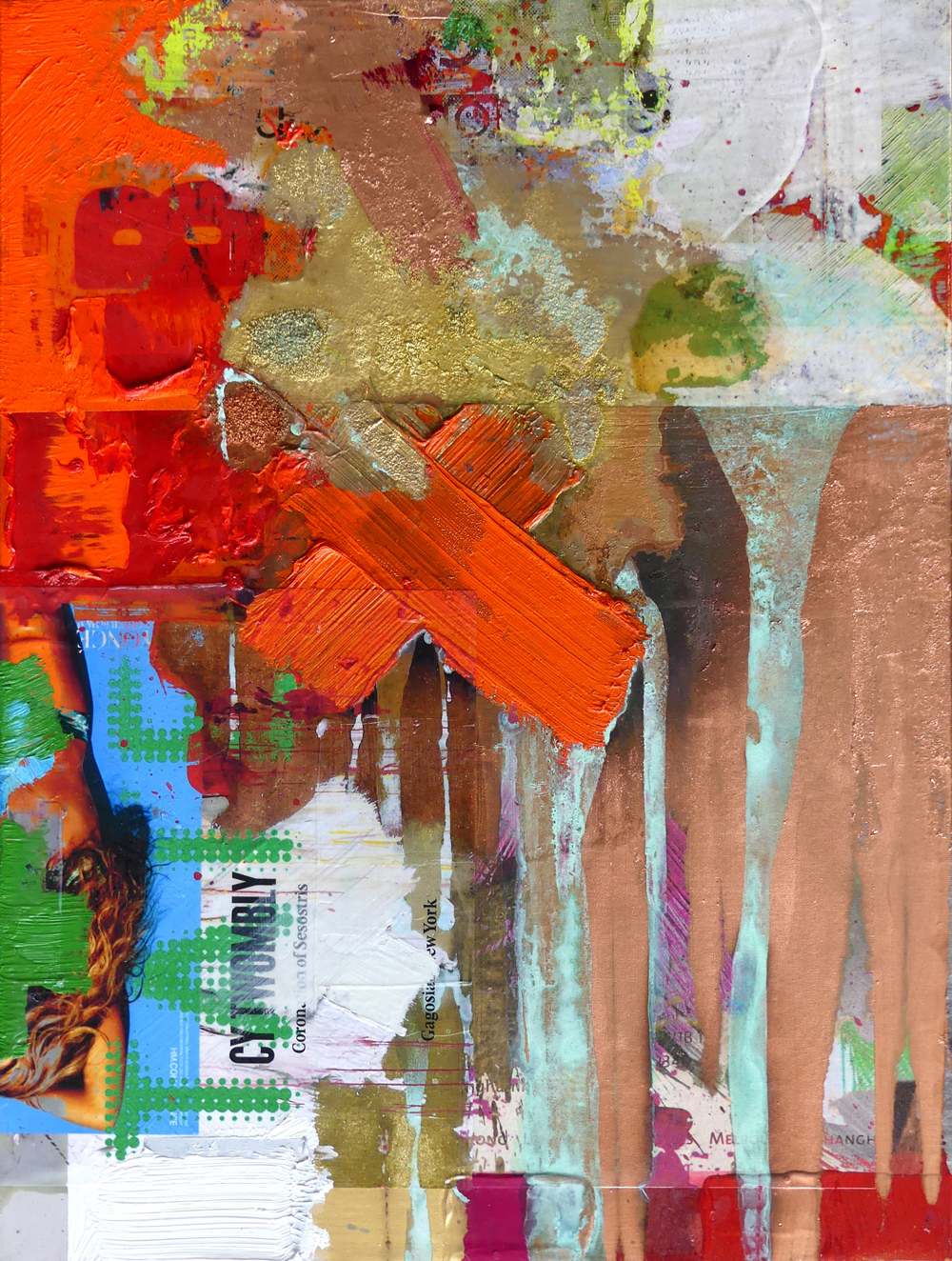

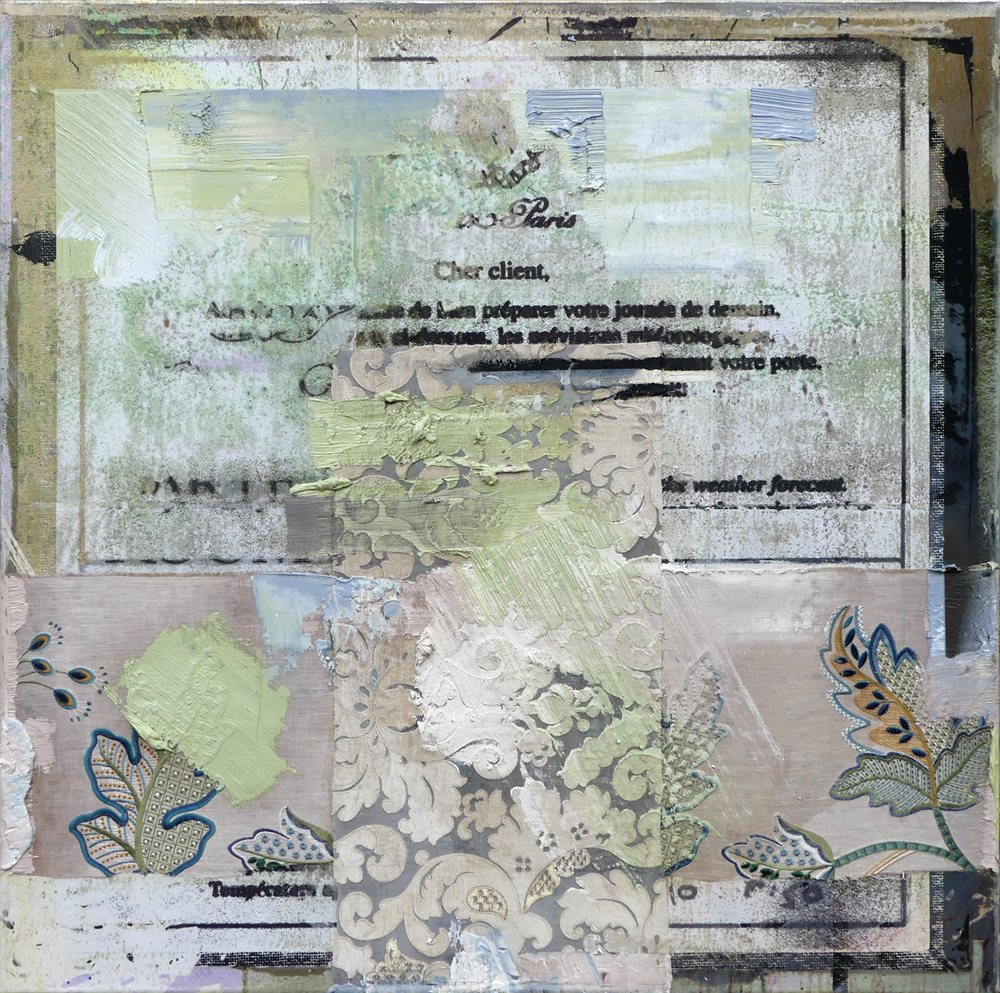

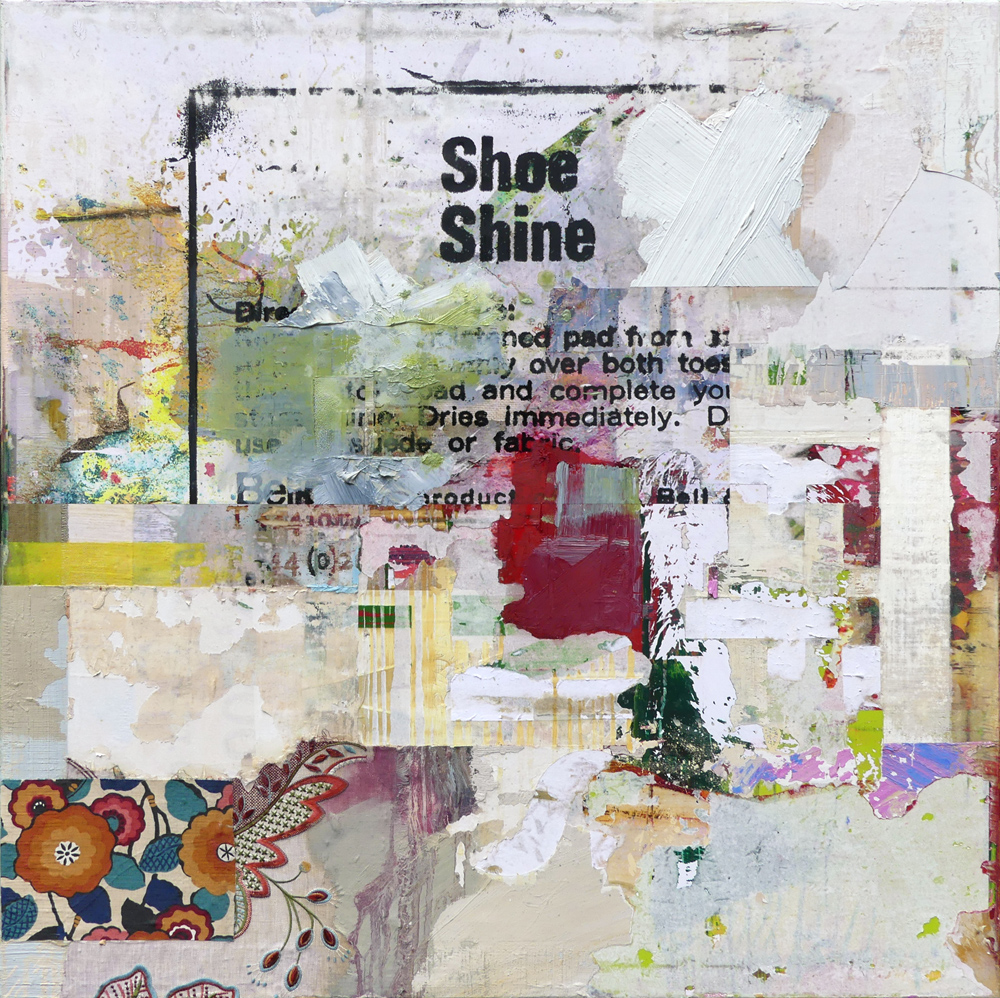

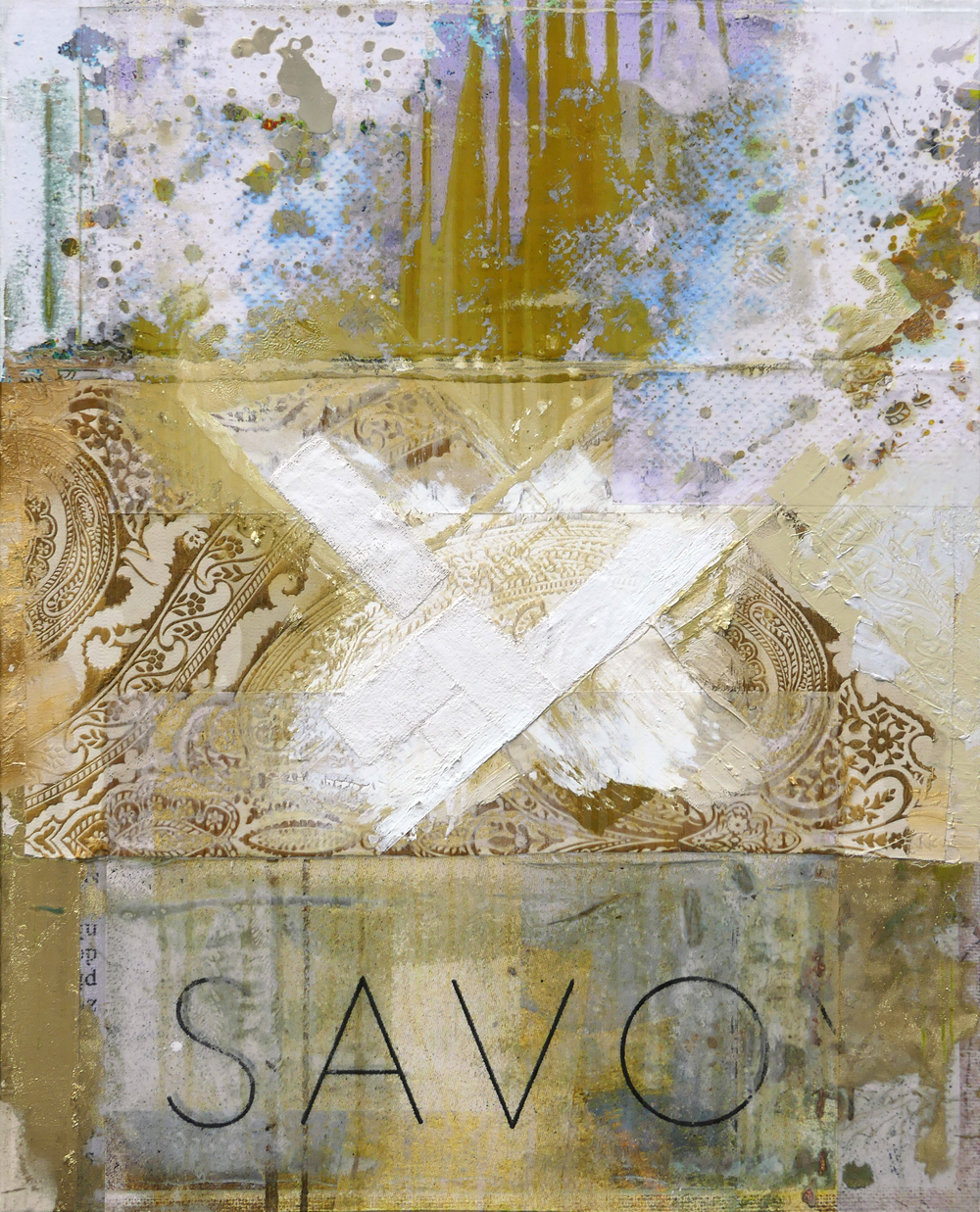

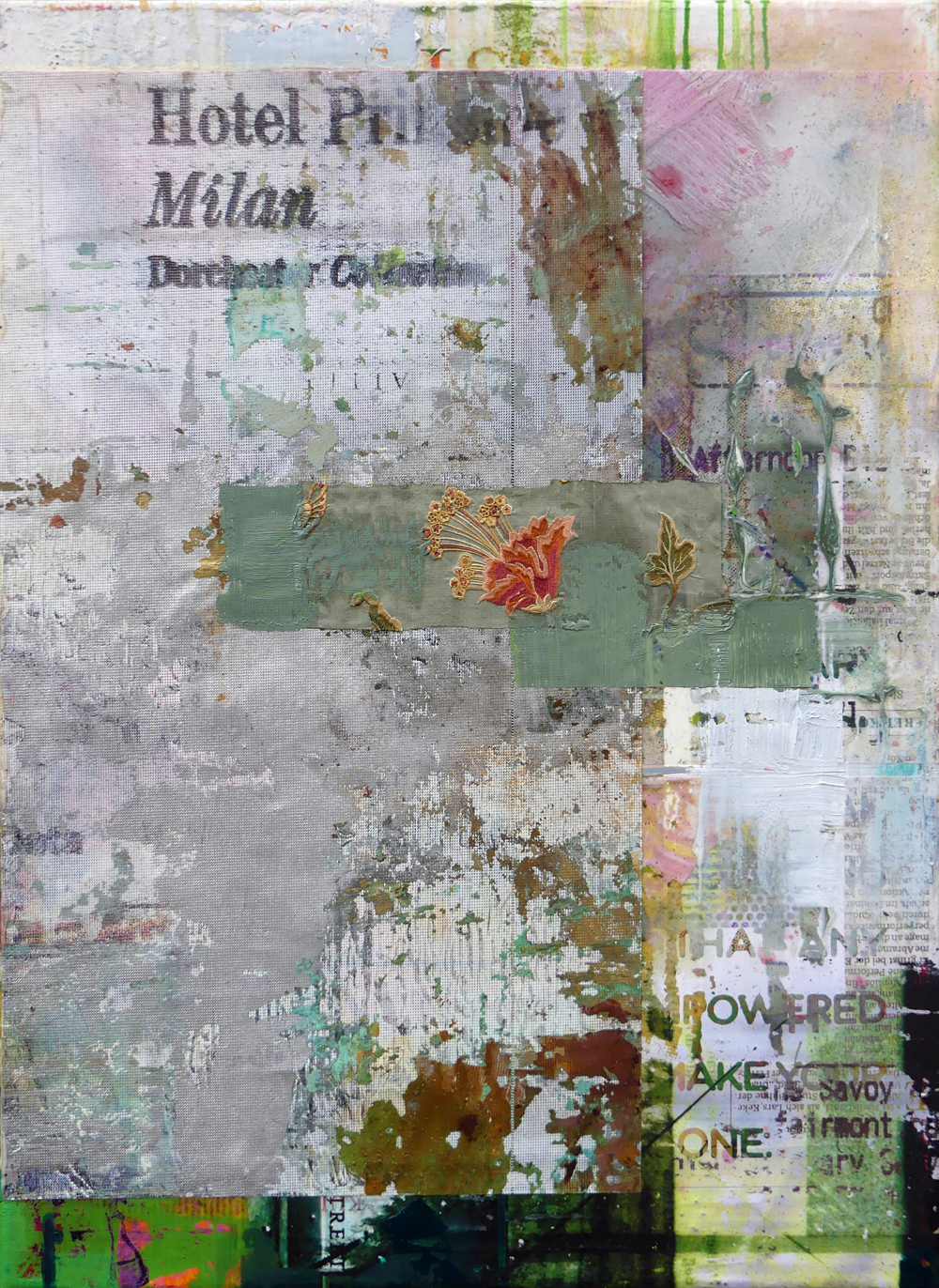

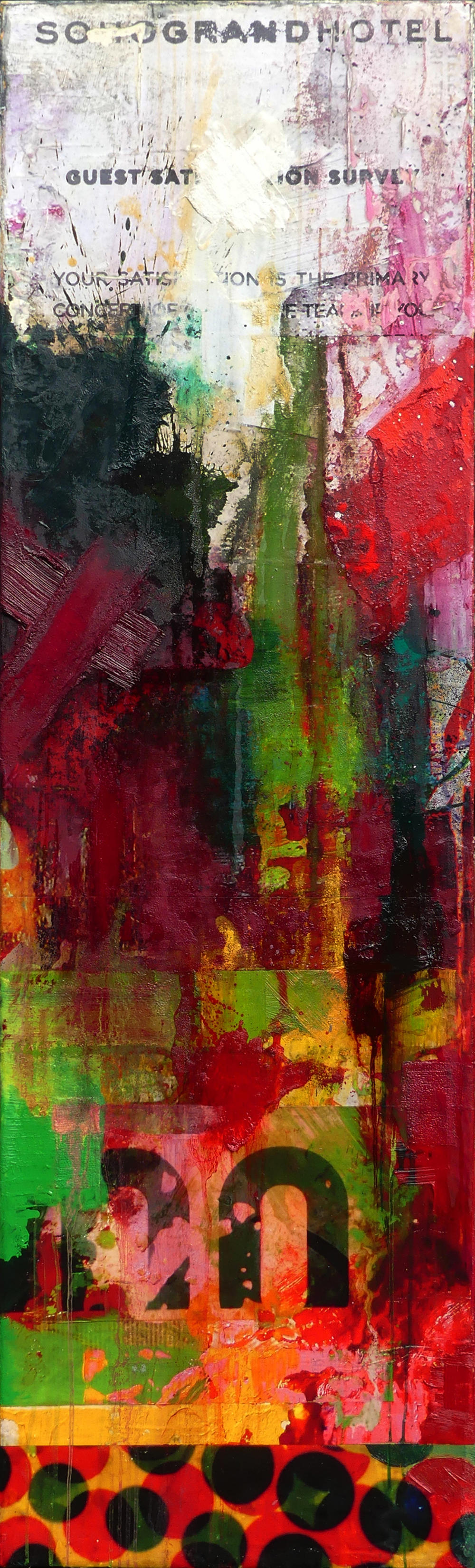

Peter Vahlefeld’s visceral artworks combine a rigorous, process-based practice, continually rethinking the possibilities of painting. Using references to a broad array of sources, including art history, literature, and pop culture, he creates paintings that alternate between flat experience and dimensionality.

Perfectly poised between European and American traditions, his work combines complexity into a visual richness that is neither figurative nor abstract. The paintings unfold in an intricate, unpredictable interaction of layers and excess. He wants to get the viewer to move past definitions and on to something more personal and fragile, a place or surface where thoughts and feelings meet, where looking feels like thinking.

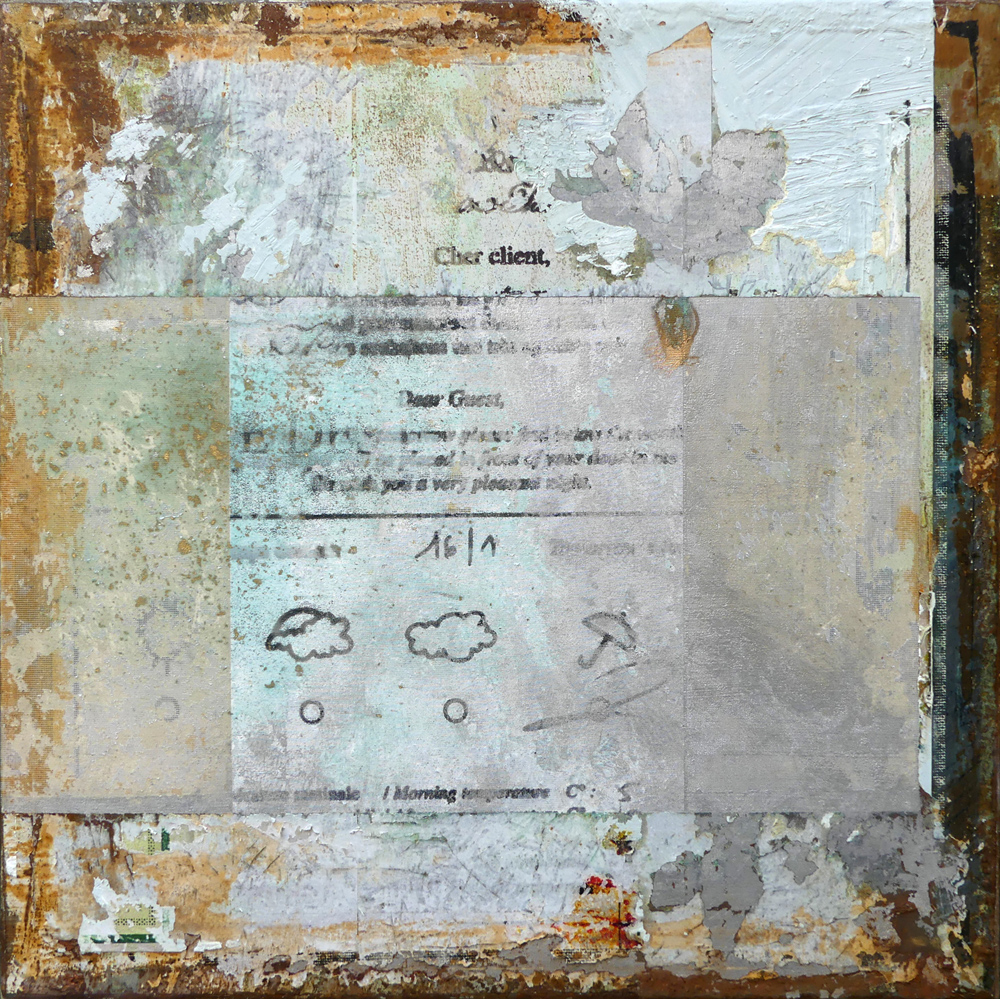

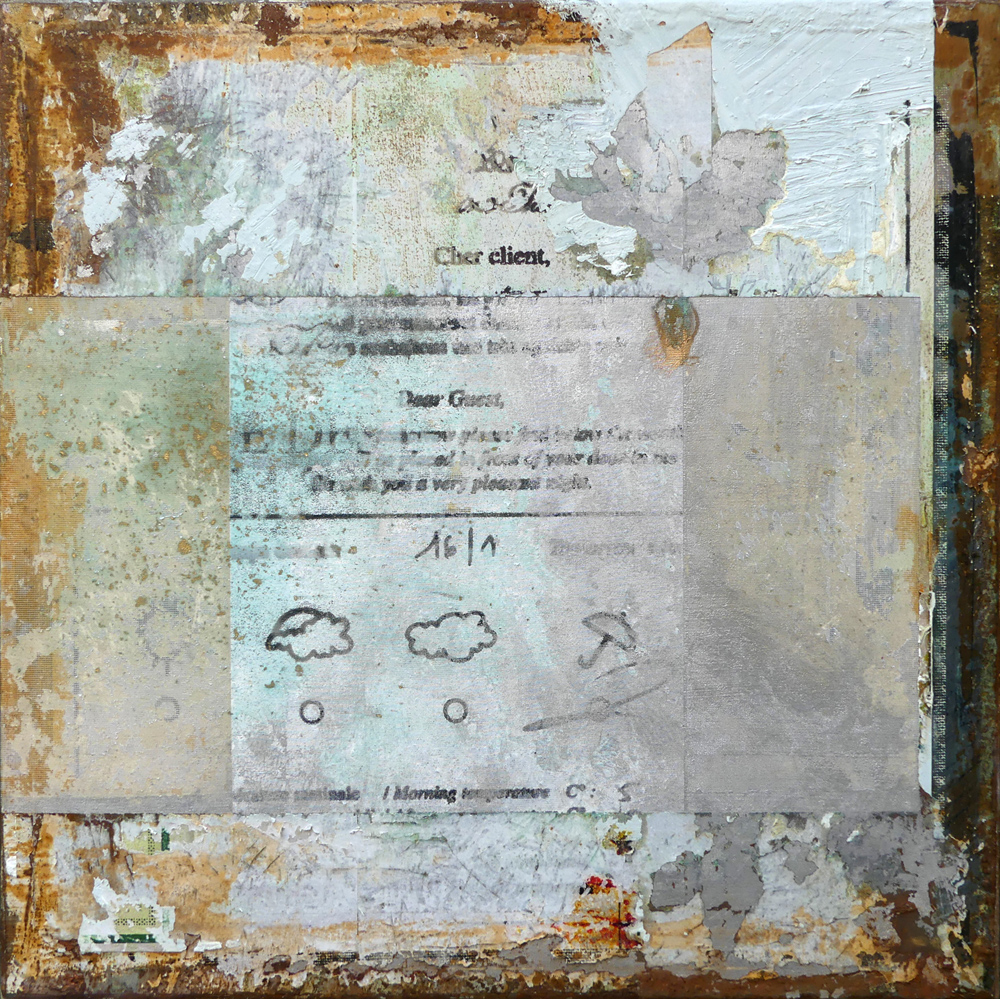

A lot of paintings have text in them at the beginning.

Mostly the text will be overpainted, but it sets a mood.

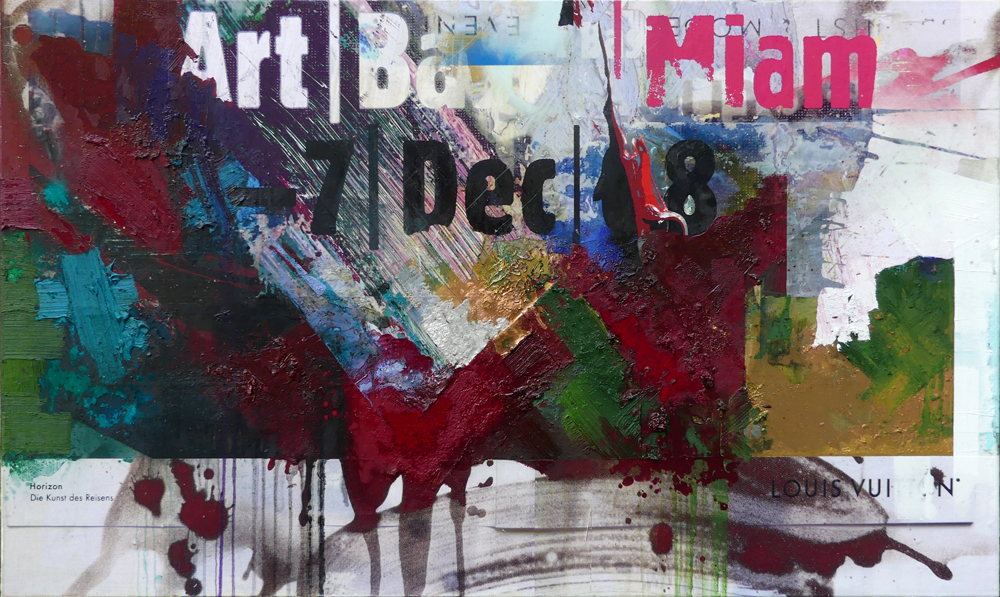

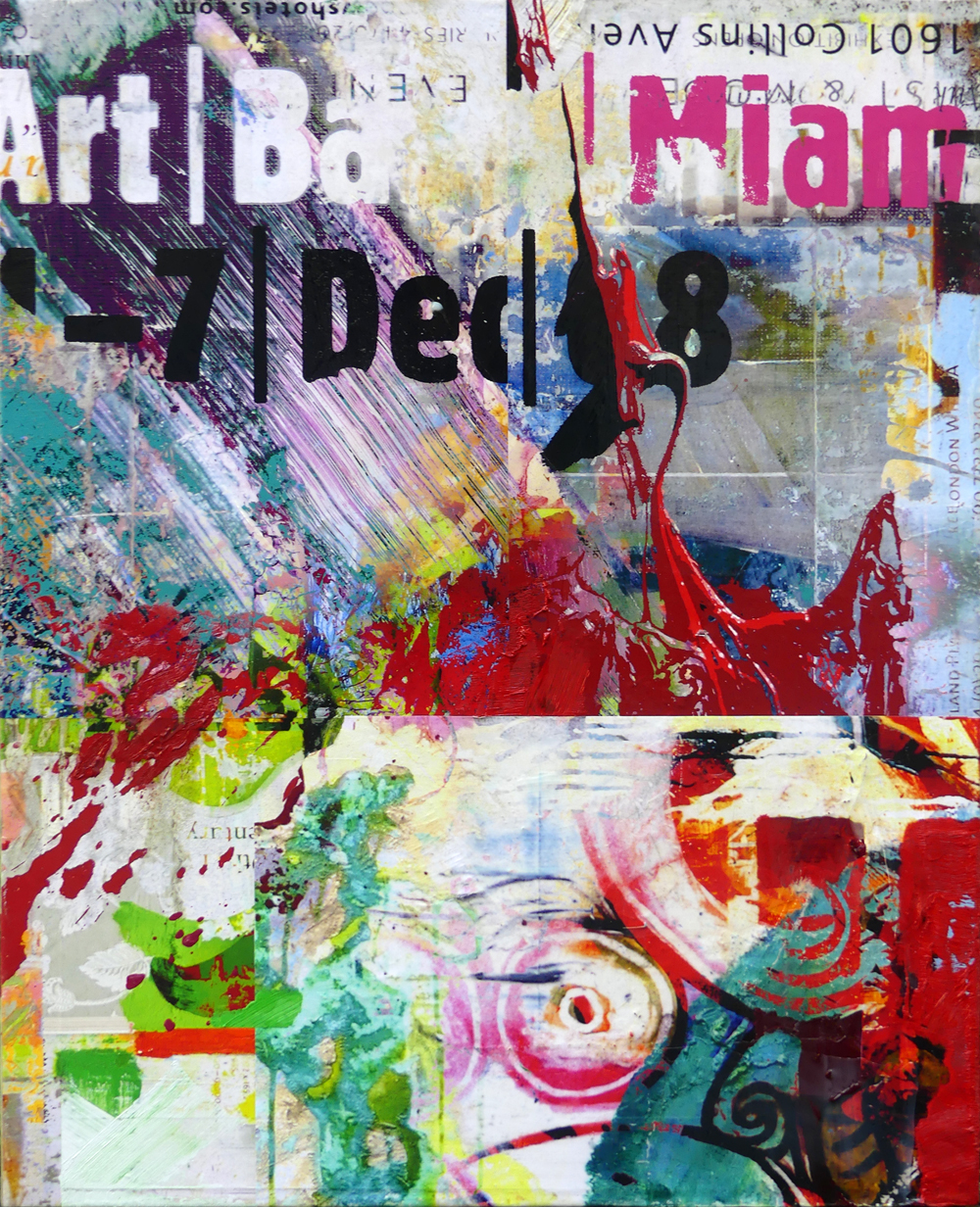

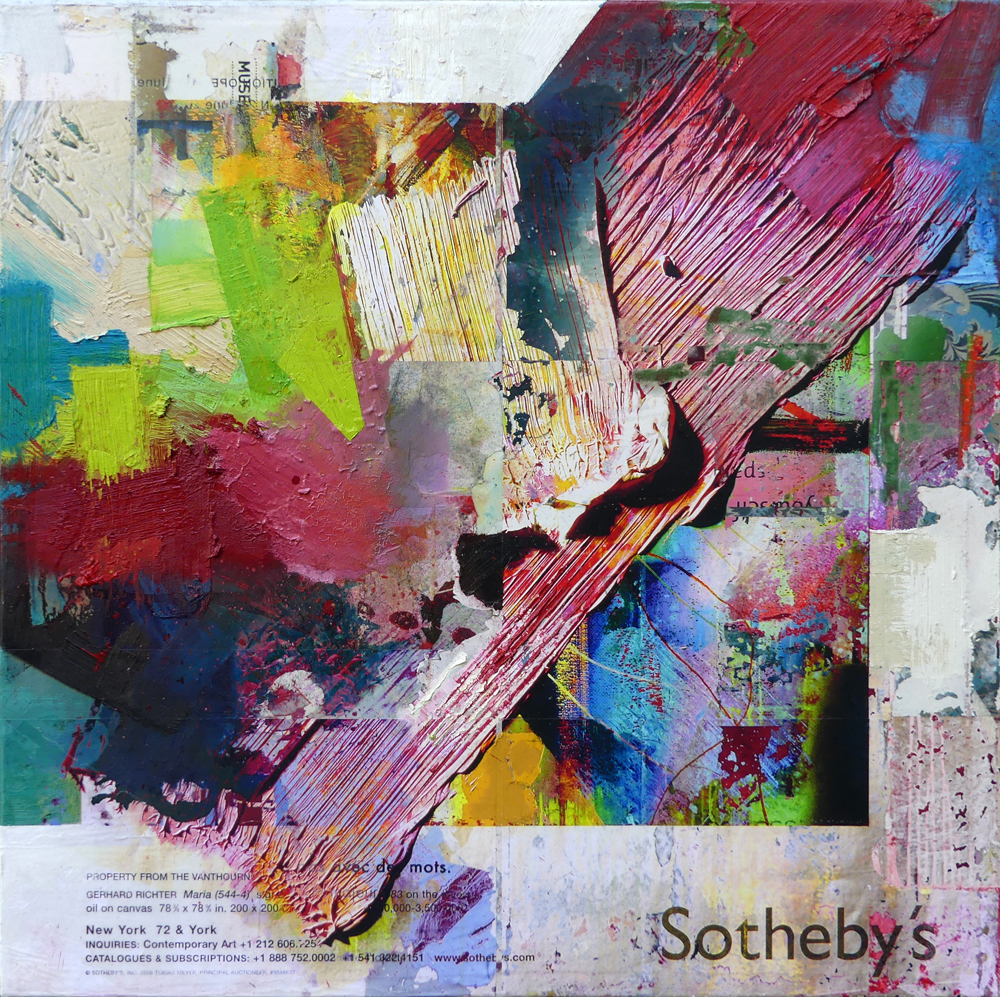

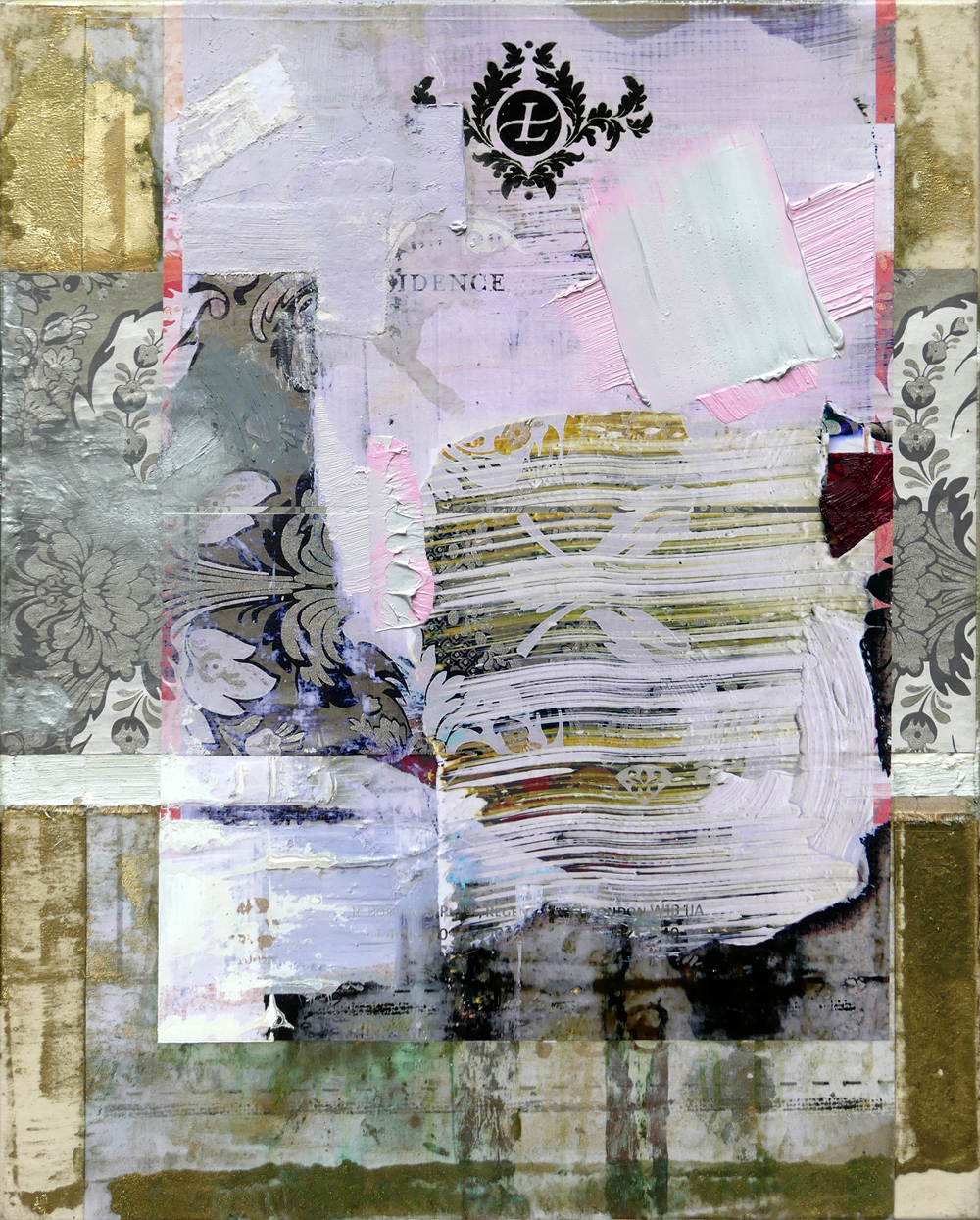

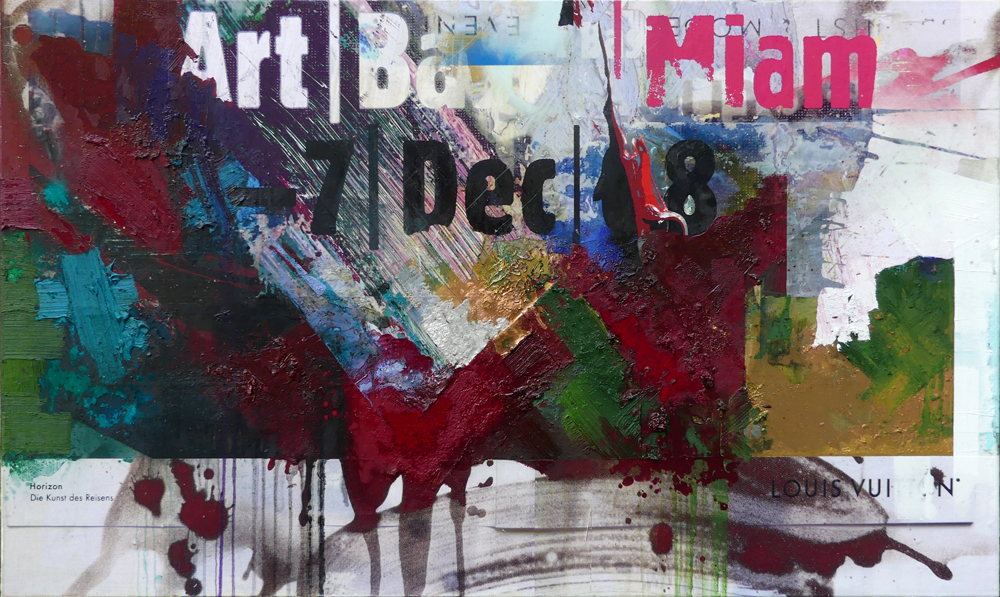

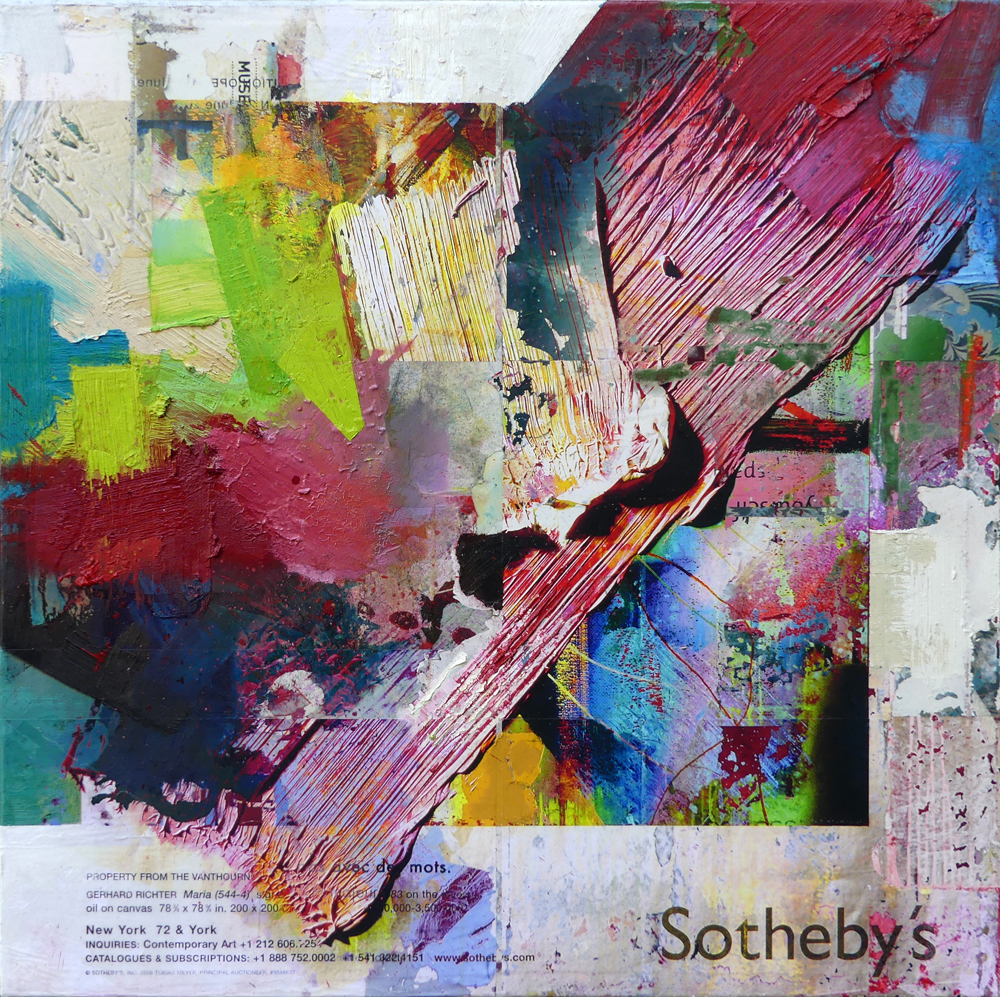

Peter Vahlefeld takes decorative forms like words, logos, symbols and fabrics to the extreme in order to recall an original canon of modern art and succeeds in turning this canon into a complex, unforeseen structure.

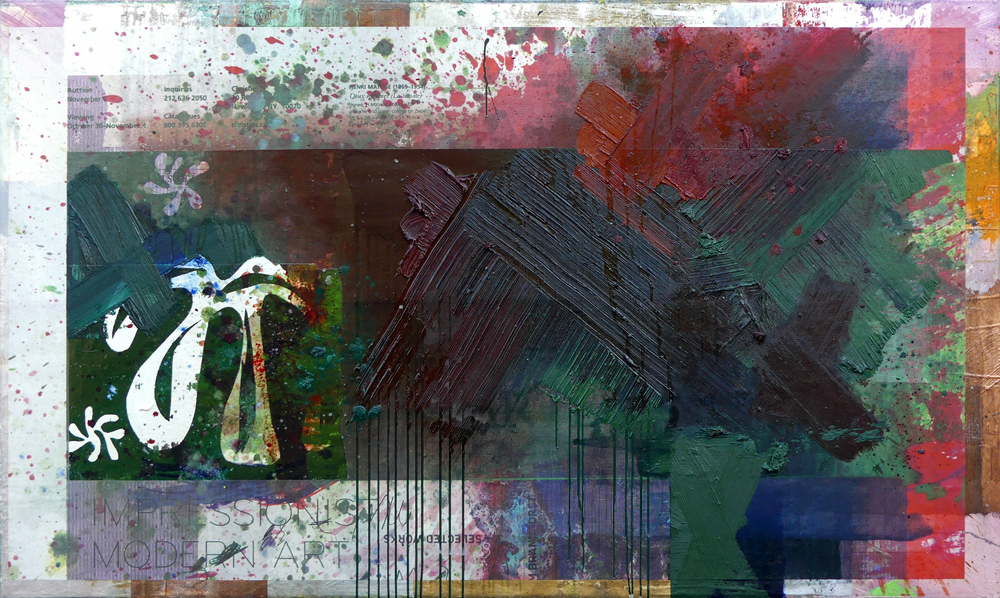

For instance, he uses elements from the classical topics of painting, which are quoted in advertisements for auction houses and galleries, and reassembles them into something new.

It is a constant juggling of different layers, speeds, and materials.

There is no way to explain it all; it’s so much intuitive technicality—a constant interaction of paint, print, fabrics, mediums and effect.

A juxtaposition of hiding and exposing, smudged with their own lost history.

This process speaks of one of Vahlefeld’s significant preferences: to introduce the painterly into the graphic, and vice versa, forcing the two modes together in a single image and then to let it go, allowing material to alchemize independently.

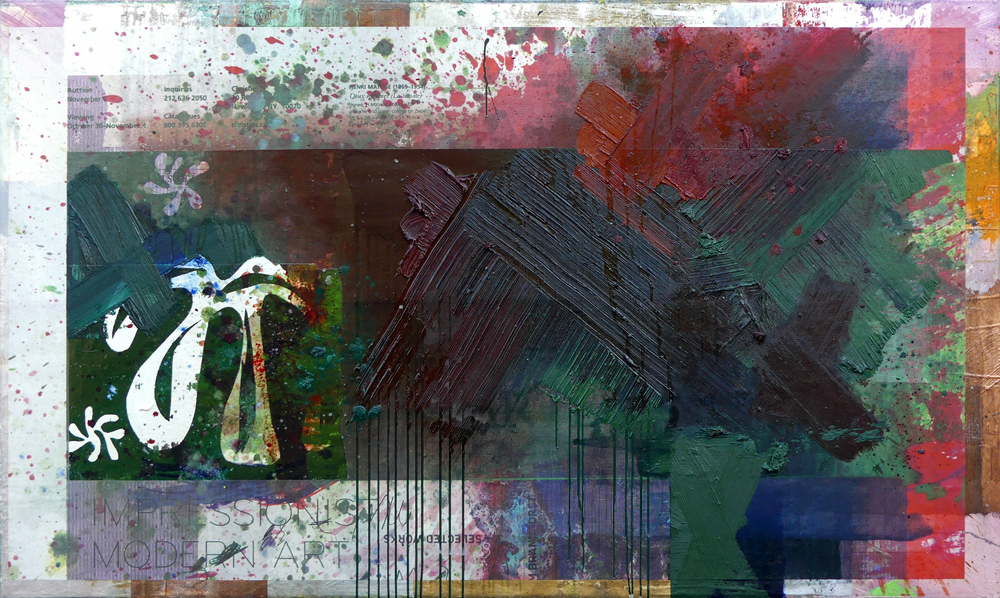

Peter Vahlefeld has always been interested in postwar painting in Germany and France, such as the work of Wols, Fred Thieler, Emil Schumacher or Matisse—as well as their american counterparts like Robert Rauschenberg, Willem de Kooning or Julian Schnabel.

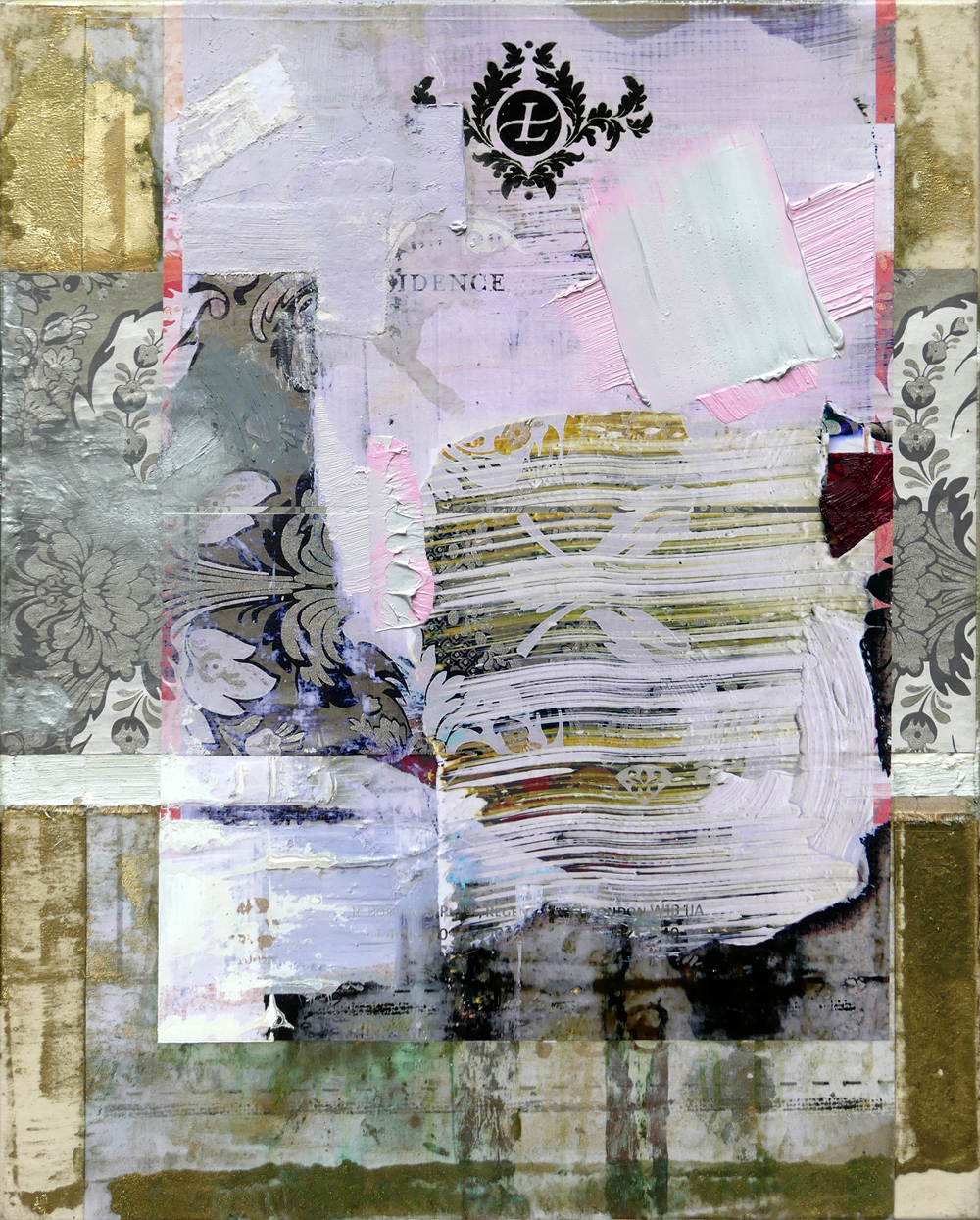

His gestural approaches intersect with references to fabrics and patterns.

His art is shaped by trying everything, treating the material without respect, using destruction as a principle, sometimes playfully, while simultaneously building up energy in the picture.

Work proceeds by means of improvisation.

Each painting has its own journey.

The process involves transformation.

Start somewhere, put it down, then move it somewhere else.

Space becomes mass and mass, void, and void, picture plane, and picture plane, paint.

Abstraction is figure and figure is ground.

He works in layers, more like a sculptor than a painter, and because he uses oil, each decision tends to involve brutal overpainting rather than gentle shifting.

It might be an unresolved conflict between finished and unfinished, messed-up and un-messed-up or between content and abstraction.

How Do We Read Images?

Peter Vahlefeld’s visceral artworks combine a rigorous, process-based practice, continually rethinking the possibilities of painting.

Using references to a broad array of sources, including art history, literature, and pop culture, he creates paintings that alternate between flat experience and dimensionality.

Perfectly poised between European and American traditions, his work combines complexity into a visual richness that is neither figurative nor abstract.

The paintings unfold in an intricate, unpredictable interaction of layers and excess.

He wants to get the viewer to move past definitions and on to something more personal and fragile, a place or surface where thoughts and feelings meet, where looking feels like thinking.

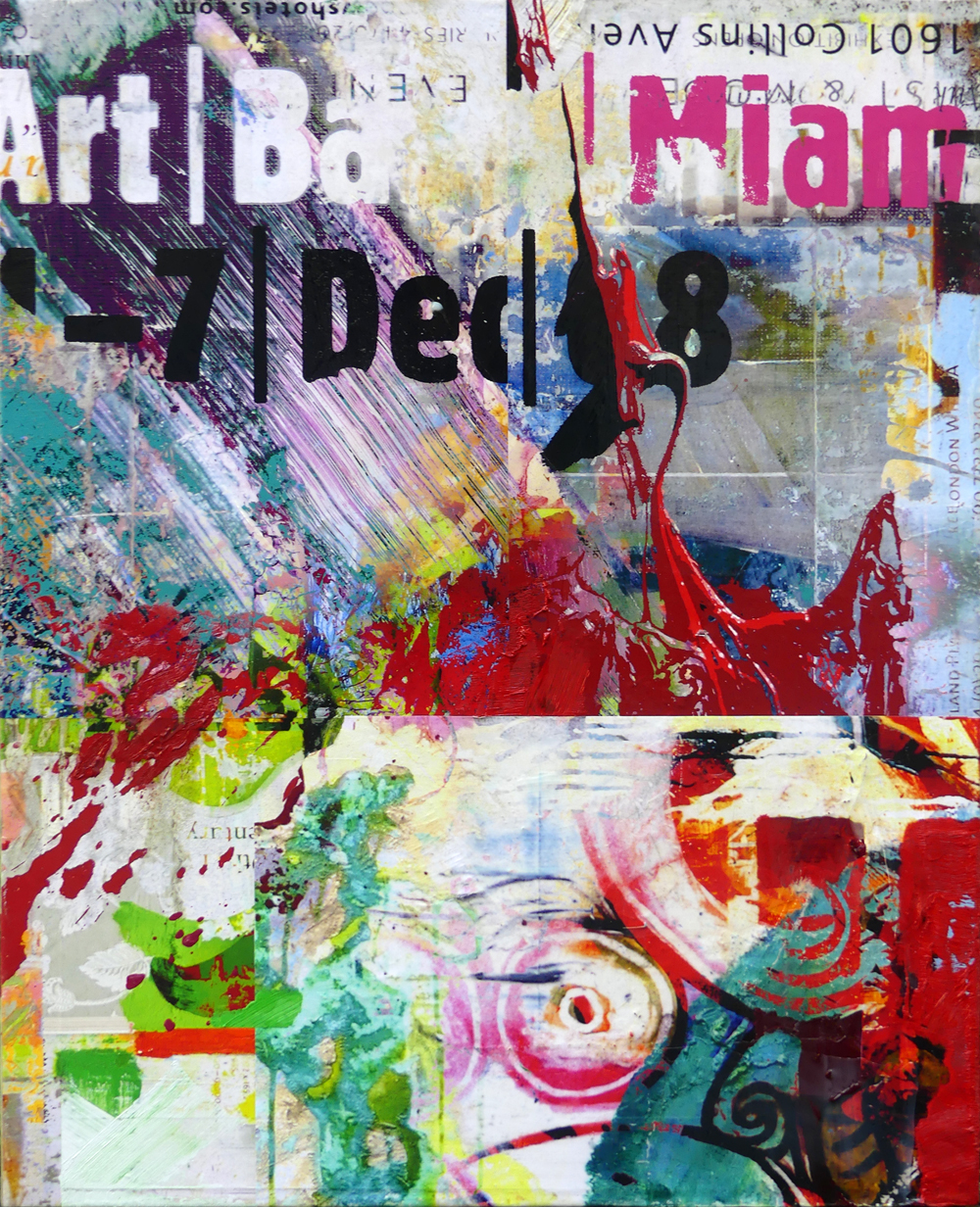

A lot of paintings have text in them at the beginning. Mostly the text will be overpainted, but it sets a mood.

Peter Vahlefeld takes decorative forms like words, logos, symbols and fabrics to the extreme in order to recall an original canon of modern art and succeeds in turning this canon into a complex, unforeseen structure.

For instance, he uses elements from the classical topics of painting, which are quoted in advertisements for auction houses and galleries, and reassembles them into something new.

It is a constant juggling of different layers, speeds, and materials. There is no way to explain it all; it’s so much intuitive technicality—a constant interaction of paint, print, fabrics, mediums and effect.

A juxtaposition of hiding and exposing, smudged with their own lost history. This process speaks of one of Vahlefeld’s significant preferences:

to introduce the painterly into the graphic, and vice versa, forcing the two modes together in a single image and then to let it go, allowing material to alchemize independently.

Peter Vahlefeld has always been interested in postwar painting in Germany and France,

such as the work of Wols, Fred Thieler, Emil Schumacher or Matisse—as well as their american counterparts like Robert Rauschenberg, Willem de Kooning or Julian Schnabel.

His gestural approaches intersect with references to fabrics and patterns. His art is shaped by trying everything, treating the material without respect, using destruction as a principle, sometimes playfully, while simultaneously building up energy in the picture.

Work proceeds by means of improvisation.

Each painting has its own journey. The process involves transformation. Start somewhere, put it down, then move it somewhere else.

Space becomes mass and mass, void, and void, picture plane, and picture plane, paint.

Abstraction is figure and figure is ground.

He works in layers, more like a sculptor than a painter, and because he uses oil, each decision tends to involve brutal overpainting rather than gentle shifting. It might be an unresolved conflict between finished and unfinished, messed-up and un-messed-up or between content and abstraction.

Peter Vahlefeld’s visceral artworks combine a rigorous, process-based practice, continually rethinking the possibilities of painting. Using references to a broad array of sources, including art history, literature, and pop culture, he creates paintings that alternate between flat experience and dimensionality.

Perfectly poised between European and American traditions, his work combines complexity into a visual richness that is neither figurative nor abstract. The paintings unfold in an intricate, unpredictable interaction of layers and excess.

He wants to get the viewer to move past definitions and on to something more personal and fragile, a place or surface where thoughts and feelings meet, where looking feels like thinking.

A lot of paintings have text in them at the beginning. Mostly the text will be overpainted, but it sets a mood. Peter Vahlefeld takes decorative forms like words, logos, symbols and fabrics to the extreme in order to recall an original canon of modern art and succeeds in turning this canon into a complex, unforeseen structure.

For instance, he uses elements from the classical topics of painting, which are quoted in advertisements for auction houses and galleries, and reassembles them into something new.

It is a constant juggling of different layers, speeds, and materials. There is no way to explain it all; it’s so much intuitive technicality—a constant interaction of paint, print, fabrics, mediums and effect. A juxtaposition of hiding and exposing, smudged with their own lost history.

This process speaks of one of Vahlefeld’s significant preferences: to introduce the painterly into the graphic, and vice versa, forcing the two modes together in a single image and then to let it go, allowing material to alchemize independently.

Peter Vahlefeld has always been interested in postwar painting in Germany and France, such as the work of Wols, Fred Thieler, Emil Schumacher or Matisse—as well as their american counterparts like Robert Rauschenberg, Willem de Kooning or Julian Schnabel. His gestural approaches intersect with references to fabrics and patterns.

His art is shaped by trying everything, treating the material without respect, using destruction as a principle, sometimes playfully, while simultaneously building up energy in the picture.

Work proceeds by means of improvisation. Each painting has its own journey.

The process involves transformation. Start somewhere, put it down, then move it somewhere else. Space becomes mass and mass, void, and void, picture plane, and picture plane, paint.

Abstraction is figure and figure is ground. He works in layers, more like a sculptor than a painter, and because he uses oil, each decision tends to involve brutal overpainting rather than gentle shifting. It might be an unresolved conflict between finished and unfinished, messed-up and un-messed-up or between content and abstraction.